In Quiapo lies a tale of colored candles, whispered wishes, and two sisters

by Mariano, Jennel Christopher A., BAJ 3-2N

In Quiapo lies a tale of colored candles, whispered wishes, and two sisters

Walking around Plaza Miranda and taking photographs of the majestic Quiapo Church, or the National Shrine of the Black Nazarene, I could not help but admire the incredible Baroque composition of the edifice. On weekends, the area is as busy as it gets. It was jampacked, with hundreds of strangers brushing sleeves as they all pass through the narrow paths of Quiapo.

Just outside the left foyer of the church, a formation of stalls and vendors that stretches to the adjacent streets offers a wide assortment of items such as ornaments, accessories and novelties. What is strikingly noticeable is the string of carts carrying colorful wishing candles, situated right where Evangelista St. and Carriedo St. converge. These are particularly hard to miss.

Quiapo is famed for the great influence of spiritualism and mysticism in the district. The vendors of the wishing candles, who are mostly friendly, elderly women, always say that the success rate of their candles is through the stars. One vendor I asked, a stout senior with silver hair, said that her buyers’ wishes have always come true.

The competition in the candle-selling business is very tight, physically and figuratively. Their stalls are set up so closely next to each other, which in turn might make consumers torn on whom to buy candles from. Nevertheless, every vendor sitting behind their stalls radiates an aura of warmth—just like the candles that they burn.

In particular, I found Nanay Ligaya, 58, to be more tender toward her younger buyers. She estimates that she has been selling candles for 20 to 25 years.

Most vendors only sell their candles in bundles for P50, a necessary strategy to earn more money in the candle-selling business. Nanay Ligaya, on contrary, kindly offered me individual candles, which she sells for P10. She said that it’s a “student price” and it’s also for those who only want to try. At the same time, she also sells bundles composed of different-colored candles.

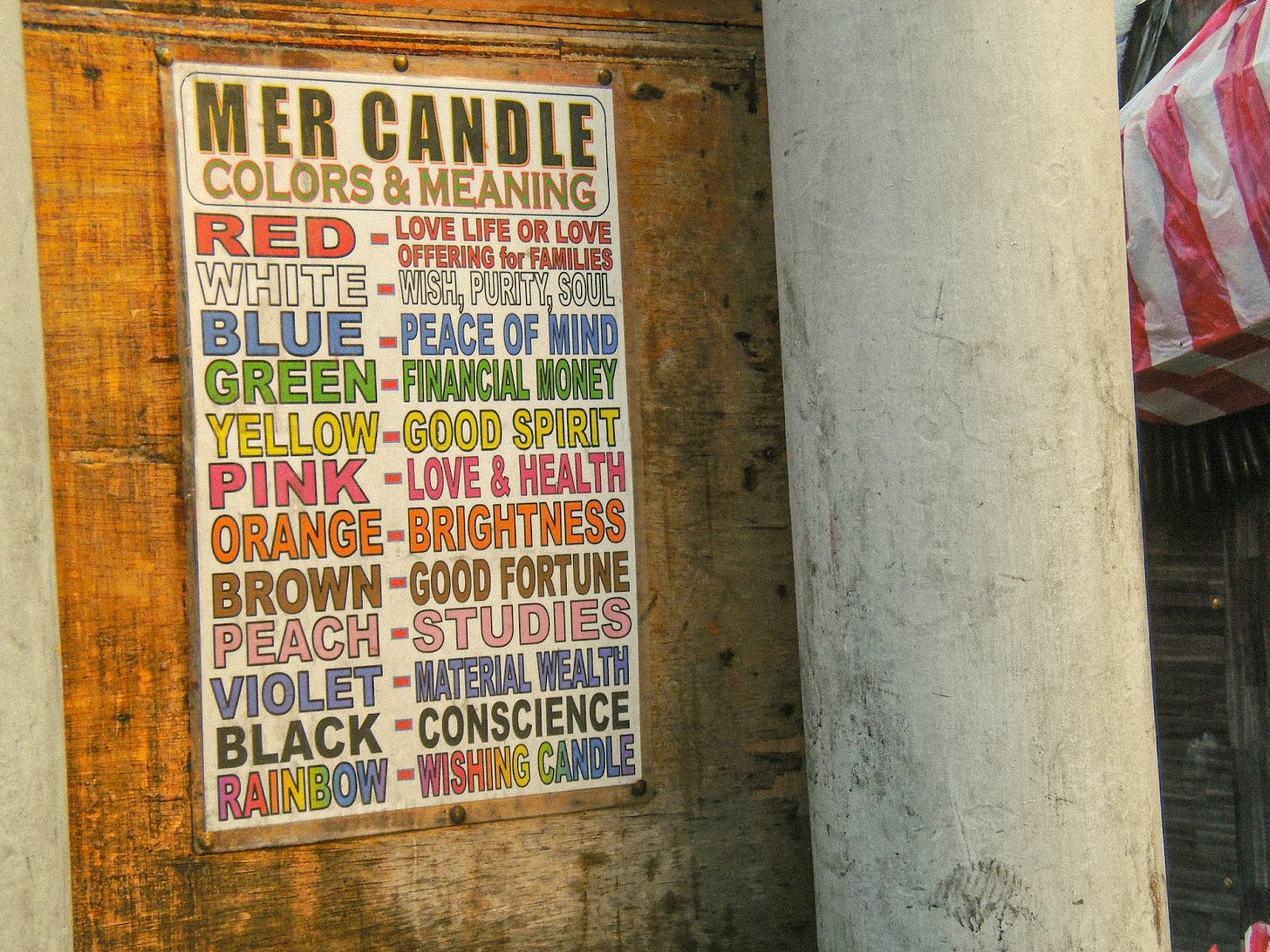

The colors that these candles bear each represent a unique aspect of life. Every stand displays a sign bearing a guide to these color symbolisms, as well as the name of their stall. For example, red represents family and health, yellow stands for the soul, and pink embodies romance.

Other colors are especially aligned with a specific purpose, or symbolize a very definite concept. Peach candles are made for students, those who seek to pass their exams or reap good fortune for anything related to their studies. Then, if you want to pay your dues to the Black Nazarene, light a maroon candle. Interestingly, they also sell black candles that are supposed to touch the conscience of those who have wronged you.

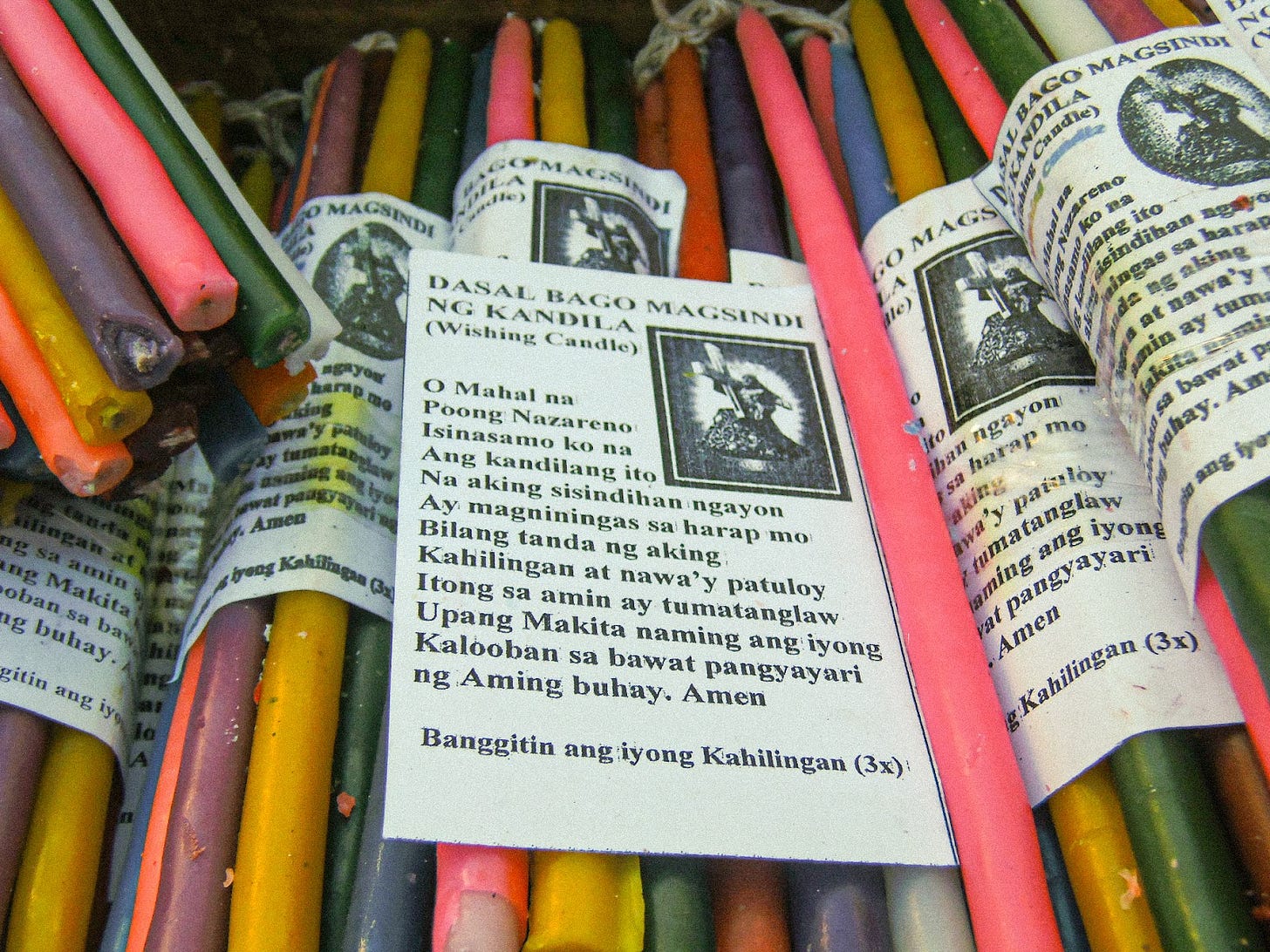

To make a wish, one must solemnly recite the prayer that comes with the candle, and right after, light the candle and let it burn until the wax melts completely—a practice that is noticeably similar to All Souls’ Day tradition. The carts also have built-in fire pits that hold the lit candles, and customers may opt to stay and watch as their wish tries to burn itself into the fabric of reality. And of course, don’t forget to hand your payment to the affable vendor, or maybe try to strike a friendly conversation with them too.

I bought a pink candle from Nanay Ligaya, who was supportive toward my color of choice, albeit she was quite surprised I didn’t pick a peach one. Unfortunately, the wind seemed to be sabotaging my wish as it kept blowing out my candle’s flame. She even joked that it might not yet be the right time for me to find romance. In my defense, I only wanted to try a wishing candle, and thought it would be absurdly funny to choose pink, as an academics-driven student.

Intriguingly, when I mentioned that I study at PUP, she asked if it was near a certain private medical college, which I know is located in Sampaloc. Curious, I asked her back if she knew anyone from that school—to which she replied that her daughter is currently a second-year student taking up nursing there.

Traveling daily from their home in Obando, Bulacan to sell candles in Quiapo, Nanay Ligaya endures her routine to support her daughter’s studies. Even so, she has acknowledged that income in the candle-selling business is weak.

Vendors like her manage to keep the life of this business despite the threat of continuous modernization because of firm believers—much like the candles that stay burning in defiance of the wind.

Most of these stalls, if not all, are in fact family-run businesses, and have been passed in a sequence of generations, she revealed. Moreover, some of the vendors there are not the actual owners of the stall, instead they are being paid to watch over the stand and sell candles. Nanay Ligaya, for one, said that she’s only a vendor at her stand, and that her sister-in-law owns it.

Despite fierce competition, the vendors get along well with each other. Nanay Ligaya appeared to be good friends with an older vendor behind her, Nanay Inday, who is in her 70s already.

During our conversation, Nanay Inday left her stall for a while, and in a riveting turn of events, another elderly woman, whose hair is still mostly black, arrived. I was delighted to know that she is Nanay Lydia, the owner of the stands that Nanay Ligaya and Nanay Inday watch over.

Or so I thought—it came to light that Nanay Ligaya was humble enough not to admit that she also owns the stand with Nanay Lydia. Apparently, that is true, as I checked the sign hanging from their stall to see both of their names on it.

The 59-year-old Nanay Lydia has been in the candle-selling business for at least 30 years. She lives in Malabon City, which is about half as far as Obando is from Manila. Wrapping her candles into bundles as we talk, Nanay Lydia’s philosophy slowly manifested itself.

The phrases “tibay ng loob” and “lakas ng loob” were her catchline, having made a gambit when she first tried to sell candles in Quiapo, as she knew the uncertainties of it. This also mirrors Nanay Ligaya’s everyday venture, where she has to keep her lakas ng loob ablaze to withstand this endeavors, however cruel.

Eventually, their stories came full circle when both of them said that, like their customers, they also light wishing candles and say their prayers—but on a daily basis before they go to work.

More importantly, both vendors have their own individual greatest wishes. On one hand, Nanay Ligaya desires nothing but for her daughter to finish college. This harkens back to her fondness for her student buyers. Her love for her daughter translates into her kindness for strangers of the same age.

Subsequently, Nanay Lydia had her heart set on an altruistic wish: prosperity for everyone. She has repeatedly demonstrated her selfless nature in helping her relatives acquire a livelihood, as it turns out that one of her children’s spouse also sells candles from another nearby stall she owns.

What weaves these stories altogether is the very concept of belief. Vendors of wishing candles manage to keep their business afloat owing to individuals who choose to believe in the promise of these objects—even without knowing whether that promise will remain empty or be fulfilled. In parallel, Nanay Ligaya and Nanay Lydia echo each other’s philosophy on tibay ng loob, which quite relates to the idea of believing in oneself. As Filipinos, spirituality is already tied to our identity. No matter one’s views on religion or the mystical, we still believe in something nonetheless.

The sun had already set when I left Quiapo. Even without the rays of the sun, Plaza Miranda remained a bustling marketplace. Entering Evangelista St., I passed by Nanay Ligaya and Nanay Lydia’s stall once more. Their smiles intact and wide, and the lit candles on their cart burning brighter all the more.

Photo Gallery